“Oh, we don’t use that New Testament translation in our work.”

It was 1990, early in my work with the Sindhi Old Testament translation team when an evangelist to his own people among the Hindu tribes stunned me with that declaration.

Hu Addleton had begun work on the common language Sindhi New Testament in 1972, and through the persistent efforts of Ralph Brown and a team of Sindhi translators and reviewers, it was completed in 1985. The Sindhi NT had been published by the Pakistan Bible Society and was being distributed in the majority Muslim province of Sindh, Pakistan. During that time there was a movement to Christ among Hindu tribes and many churches were planted. I had imagined that the newly published NT in easily accessible Sindhi would play a key role in making disciples of these tribes, and so I was shocked to find that the translation was not being used.

“Why don’t you use it?” I asked.

“Because it is full of Islamic names and terms, and Hindus find this offensive,” was the reply.

A Bible translation that resonates

His honesty helped me realize that it is not sufficient to produce a translation that is clear and understandable, it must also resonate with cultural and religious norms. If we ignore that reality, the translation may not be accepted and years of careful translation effort would be wasted.

The terminology used in any translation comes with “baggage” that impacts readers on different levels, including emotional, political and intellectual.

Hindus and Hindu-background believers in the Sindh read Scripture from their position as marginalized people dominated by the Muslim majority. So even though the meaning of the text might be plain, the Islamic religious terminology used in the Muslim Sindhi New Testament creates an emotional reaction of distaste and rejection. The message is clouded by their reaction to the words used to communicate that message. Consider the reaction if a pastor read John 3:16 in this way in an average Canadian church: “For Allah so loved that world that he gave…” (Allah is used by many Christians worldwide to refer to God, e.g., Malaysia).

Bible translation for distinct religious groups

I continued the conversation with my evangelist brother wondering, “How do you give the gospel to Hindus if you can’t read the Sindhi New Testament to them?”

Pakistan is a country of 90+ languages. The national language is Urdu, the regional language of the Sindh province is Sindhi, and within the Sindh are many tribal groups each with their own distinct language. In the Sindh, the language of commerce and schooling is primarily Sindhi, with significant use of Urdu as well. When tribal Hindu groups meet, the common language used is Sindhi. However, among Protestant believers, the most popular Bible is in Urdu, a well-crafted formal version that is often difficult to understand even for Urdu mother-tongue speakers. For Hindu tribal people, many of whom are illiterate, Urdu is, at best, their third language. So I was disturbed by his answer, “We read to them from the Urdu Bible and then explain what it means.”

The insufficiency of this answer and the need for a Bible translation that resonates with Hindu Sindhi speakers bothered me as we continued work on the Sindhi Old Testament translation (geared towards a Muslim audience) until its completion in 2007. At that time, a team was formed for the creation of a Hindu Sindhi New Testament in parallel with a revision of the Muslim Sindhi New Testament. The hope was to prepare a New Testament translation with two versions geared to different audiences, yet similar enough that in joint meetings of believers there would be unity in the form, style and phrasing of the text.

Bible translation for distinct sub-cultures

We had the added complication of creating a Hindu Sindhi version that would be acceptable to, and helpful for two different groups: the tribal Hindu background believers whose mother tongue is not Sindhi, and those (not from a tribal background) whose mother tongue is Sindhi. Our team consisted of an experienced Muslim Sindhi who had worked for many years on the common language Sindhi New Testament, a Hindu mother-tongue Sindhi speaker, and a Hindu-background tribal evangelist who is fluent in Sindhi as his second language. I led the team as the “exegete” who was responsible for engaging the scholarship and resources to ensure an accurate translation. Our goal was to work together to prepare a version of the Sindhi New Testament that was suitable for a Muslim audience, as well as a version that would be acceptable to both mother-tongue Hindu Sindhis, and believers living in the Sindh who were from a tribal Hindu Sindhi background.

Bible translation process

The first common language New Testament (1980) was completed without the aid of computers. The new Hindu Sindhi NT translation and the revised Muslim Sindhi NT translation have had the advantage of powerful Bible translation programs as well as access to many resources and scholars (including Northwest’s own Dr. Larry Perkins).

The translation was done in stages: several chapters of the 1980 Sindhi NT were sent to Hindu Sindhis so they could suggest alternative terms for Islamic vocabulary. Hindu terminology for words like God, son, spirit, almighty, promise, prophet, apostle, grace and love were suggested and a draft translation was created. Two members of the team read through the text and made grammatical corrections and other adjustments suitable for a Hindu audience. Then came the hard work of doing an exegetical check on both versions, slowly and carefully rephrasing the Sindhi for clarity and accuracy through the whole New Testament.

Celebration!

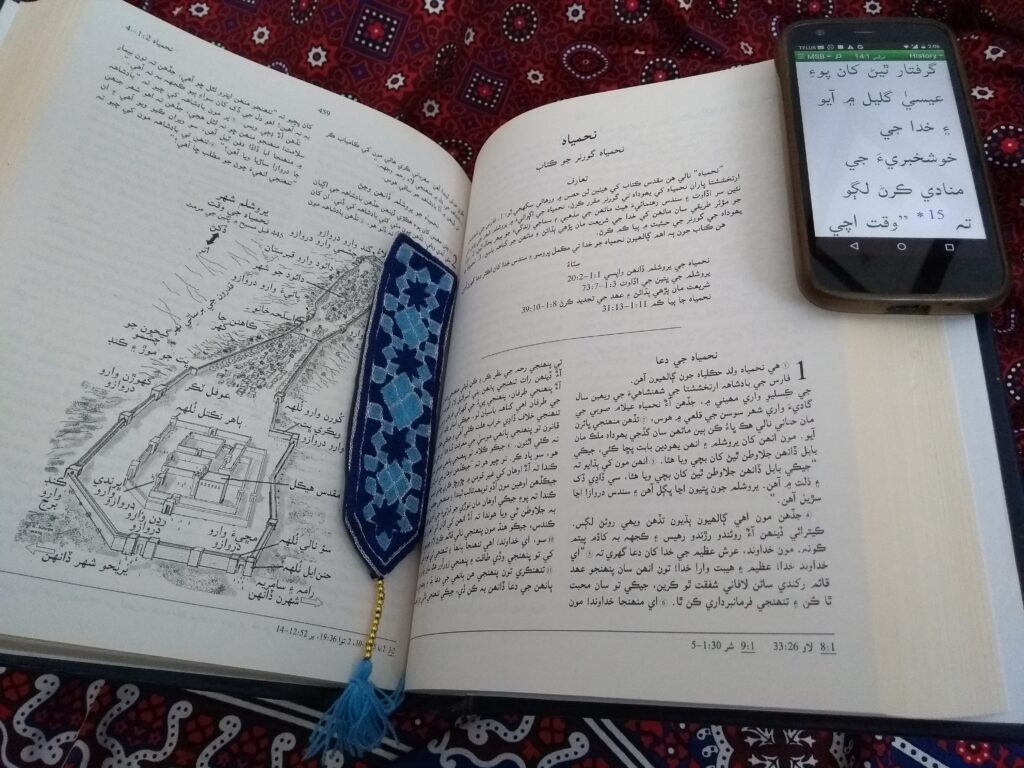

And now we are ready to celebrate! The Hindu and Muslim versions of the common language Sindhi New Testament have been completed in the fall of 2021 and are ready for publication. Both versions are now freely available for Android devices through the Kalaam i Muqaddas app, and printed versions will be also be available.

We pray that God will use his word powerfully among the people of Sindh leading many to become followers of Jesus.

Mark Naylor is Coordinator of International Leadership Development (CILD) with both Fellowship International and Northwest Baptist Seminary @ Trinity Western University (Langley BC). He and his wife, Karen, served as missionaries to the Sindhi people in Pakistan with Fellowship International from 1985-1999. Mark works part time on Bible translation projects in the Sindhi language through Zoom and occasional trips to Pakistan. His primary responsibility is the professional development of Fellowship International (FI) missionaries so that they may be “Competent as Intercultural Change Agents” (CICA) in countries where FI missionaries serve. He oversees training for intercultural disciple making through the Northwest Immerse program.